Mental and emotional disorders present challenges on two fronts: dealing with the disorder itself, and dealing with stigma attached to the disorder. Public understanding has come a long way in recent decades, but it’s still easy to find people who assume that:

- Someone with Down syndrome or developmental delays can’t learn anything that requires more than kindergarten-level skills.

- People with autism could behave “normally” if they wanted to: they just use the diagnosis to excuse irresponsible and rude behavior.

- Everyone with mental illness is prone to violence.

Unfortunately, grains of truth help keep such ideas alive. People with developmental delays do have more difficulty learning—but that’s no excuse for imposing predetermined limits on any individual. Most people with autism can learn self-control—but they still need allowances for the extra stress of trying harder.

Struggling to Live with the Pain

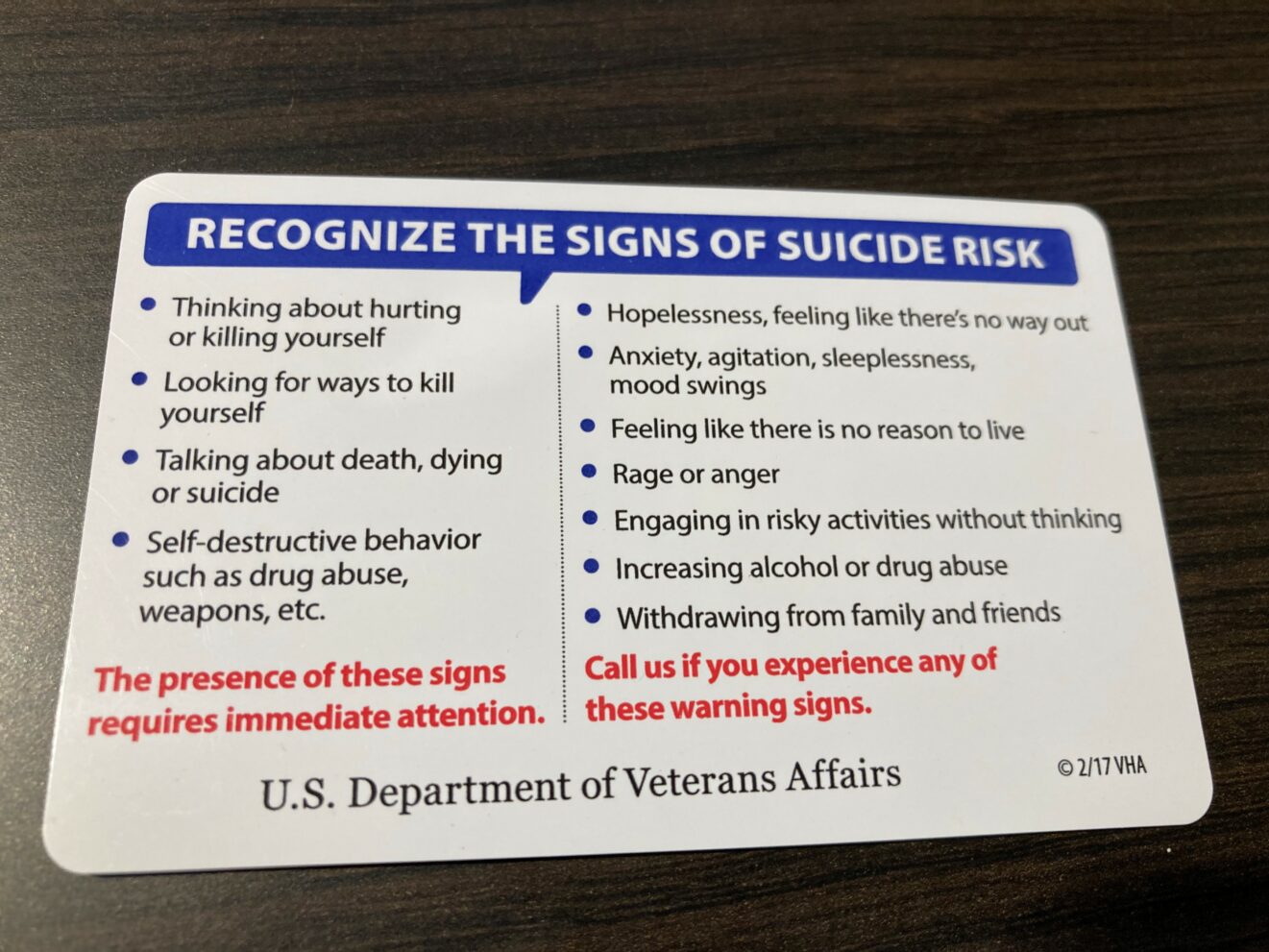

And people with mental disabilities are no more dangerous to others than is the average person—but many disabilities make people a danger to themselves. For example, people with autism spectrum disorder suffer twice as many fatal accidents as the general population. Many of these are likely deliberate “accidents,” since those “on the spectrum” are three times as likely to attempt suicide. Some disorders raise the risk even higher: around half of people with bipolar disorder make at least one suicide attempt, and nearly one in five will eventually die by suicide. Of the 45,000 suicides in the U.S. each year, 90 percent of the casualties have shown symptoms of mental illness, and 46 percent had a diagnosed mental health condition.

(Note: Suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts are also high in the LGBTQ demographic—which, like the mental-illness demographic, struggles with an additional burden of widespread stigma.)

Other people with mental disorders seek relief through “self-medicating”—using unprescribed drugs, or misusing prescribed ones, to numb physical or emotional pain. Sometimes this proves as deadly as an active suicide attempt: over 100,000 fatal drug overdoses were reported in 2021.

What Is a Dual Diagnosis?

Using drugs without medical supervision also means the possibility of developing substance use disorder (addiction to one or more drugs). About half of teens and adults with mental disorders also have substance use disorder—and vice versa. Medically, this situation is called “dual diagnosis” or “co-occurring disorders” (not to be confused with having multiple physical or mental-emotional disabilities without drug use).

There’s not always a clear connection between mental disability and substance addiction, but it’s known that:

- Drug abuse frequently leads to brain damage (not to mention other major health problems); and

- Coping with mental disorders (and the stigma surrounding them) is stressful, and stress is a serious risk factor for developing drug addiction.

It hardly needs to be said that addiction is also widely stigmatized. Especially since continued drug use involves deliberate action by the person affected, many find it hard to grasp the near-impossibility of “just stopping”—or the true dangers of cold-turkey withdrawal, which can trigger seizures, hallucinations, panic attacks, or vomiting to the point of dehydration.

What to Do about It

Anyone suffering from mental illness and/or substance use disorder needs professional medical treatment. Unfortunately, sufferers often waste months or years denying that anything is really wrong. Here again, stigma is usually part of the problem: “If I admit I can’t handle this, I’ll look like a weakling and probably lose my reputation/friends/job.”

It may help to know that:

- You can’t legally be fired for seeking treatment for a diagnosed medical problem—even if treatment includes multiple weeks of medical leave.

- You aren’t required to go into detail with anyone except your doctors.

- You’ll be a much better employee/friend/family member after you’re treated and in recovery.

- Treatment—especially addiction detox—is rarely pleasant, but trained medical specialists can help keep it bearable.

- Proper rehab will introduce you to peers who will assure you you aren’t alone in your struggles.

When you go for treatment, be prepared to:

- Choose an accredited hospital with a solid reputation.

- Be completely open about your struggles, needs, and concerns.

- Follow rules about what and what not to bring (e.g., no fragrances, out of respect for potential allergies among fellow patients).

- Plan—and participate in—a long-term program to avoid relapse (which can happen with physical and mental illnesses as well as drug addiction).

Closing Note: To Family Members and Caregivers

If you suspect that a loved one has mental illness, a drug problem, or both, your first instinct may be to “protect” them by cleaning up their messes and accepting “It won’t happen again” promises. Don’t. That only enables the problem to continue (and worsen) indefinitely.

Don’t try to nag or bully them into getting help, either. You can’t force someone else to change; but you can state your own boundaries and stand by them. (“I won’t excuse your absence to your boss for you. I will bar you from the house/bank account if you ‘borrow’ money again.”) Expect that your loved one will test those boundaries to the limit, but keep reminding yourself that you’re doing this out of love, that the goal is to give your family member every possible motivation to take action toward recovery.

Do get professional counseling and a support network for yourself—and that goes for any family member of anybody with any disability. The truth “you can’t handle it alone, and that’s okay,” applies to every person with a stake in a loved one’s recovery: facing and meeting special challenges is always a team effort!

See also:

- Apps related to medication, stress management, telehealth, and therapy

- Information on National Recovery Month

- Information on Suicide Prevention Awareness Month

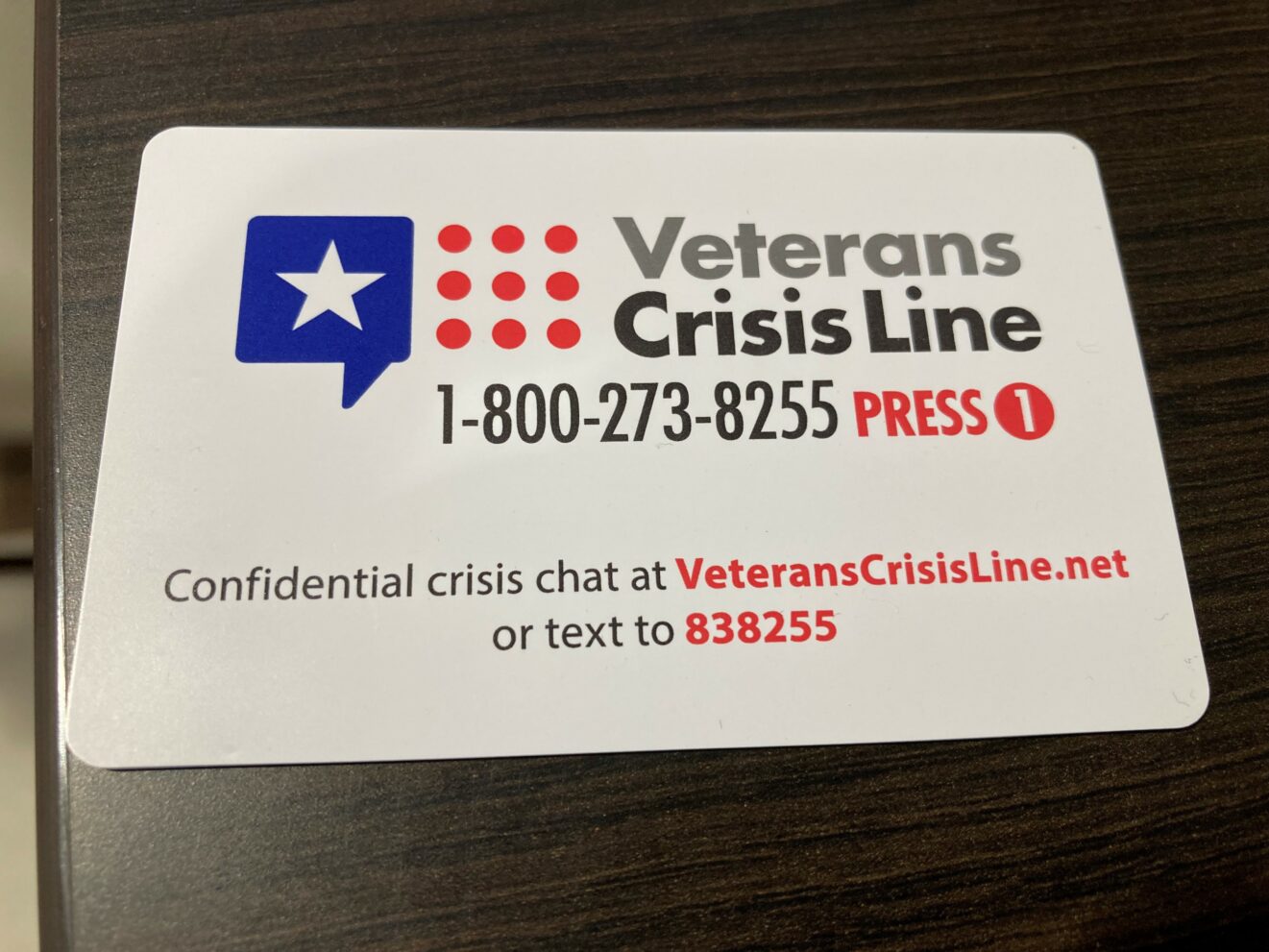

- Information on the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline