October is Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Awareness Month. AAC is assistive technology that provides audible voices for people who have disabilities impairing physical speech.

There are many reasons a person may not be able to speak physically:

- Loss of natural voice due to stroke or degenerative muscle disease

- Injury to vocal cords or throat

- Autism or intellectual disabilities that keep the brain from learning how to physically translate thoughts to spoken language

- Congenital deafness, which means that a child can’t learn speech by hearing and imitating others

The Evolution of Assistive-Technology Speech

Text-to-speech devices for the general market date back at least to the 1980s. The earliest versions were small computers that did little besides translate typed words to synthesized voice. And the voices were very obviously synthesized: flat, mechanical, no chance of passing for a human speaker.

As synthesized voices became more humanlike, another dissatisfaction arose: there was little variety in the range of voices available. Imagine being the little girl “represented” by a too-adult voice; the burly man who finds his AAC voice embarrassingly high-pitched; or the proud African American forced to “speak” with a white accent.

And matching voices with a person’s overall appearance is only part of the challenge. For those who lose speech later in life, the pain of loss can be amplified by having to use a voice that, however appropriate to your age, ethnicity, and gender, “just doesn’t sound like you.”

Enter the next stage of text-to-speech technology, “voice banking.”

Converting Natural Voices to Synthesized Speech

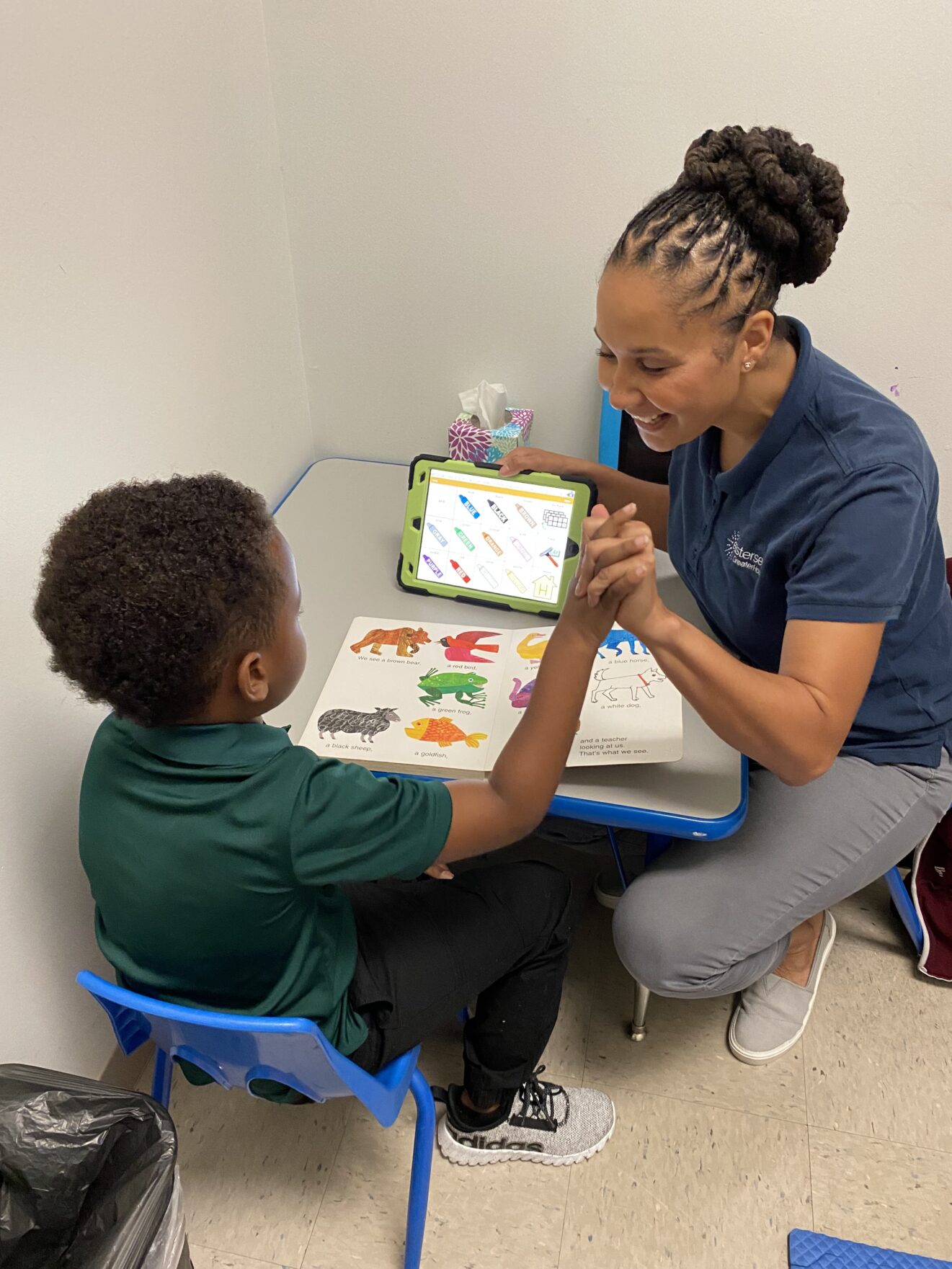

“Voice banking is a newer development that allows users to record their own voices for use on their devices,” says Daryn Ofczarzak, Speech Language Pathologist at BridgingApps/Easter Seals Greater Houston. “This is a great option for ALS clients who may have stronger voices and better vocal quality, but will eventually rely on digital voice as their disease progresses. While some voice banks work from a suite of voices, others have the option to record yourself, which I’ve found is especially appreciated by non-English-speaking families.”

Acapela Group is one voice-banking service that works with recordings of the client’s own voice (for voiceless clients, they recommend using the voices of close relatives). Other advanced-text-to-speech companies include VocalID and Control Bionics.

Finding Your Best Voice

Specific assistive technology for your family is of course an individual choice, influenced by many other factors:

- Ease of use

- App features

- Personal preferences on tone or accent

- The extent of speech loss (many people have functional speech they can’t use all the time, due to disabilities that impair breathing, pronunciation, or the ability to continue speaking for long periods)

Daryn Ofczarzak suggests looking for options that are comfortably portable and that “easily navigate to find a target word; let you program or customize additional vocabulary; and can use various languages with a ‘native speaking’ voice.”

In Closing: Etiquette Tips for Non-AAC Users

- Don’t finish anyone else’s sentences, even if their AAC speaker is slow.

- Don’t assume that speech disorders and deafness automatically go together; and never raise your voice to someone without being asked. (For many people with nonverbal autism, loud talk is worse than annoying: it triggers painful sensory overload.)

- Never ask to borrow an AAC device to “see how it works.” With assistive technology, that’s tantamount to asking someone to tape their own mouth shut.

- Be careful how you refer to speech disorders, and especially avoid phrases that start with “can’t”: “can’t talk,” “can’t communicate verbally,” etc. Many people consider AAC a form of talking, and most everyone would rather be acknowledged by how they can communicate.

- Pay attention to what’s being said, not how it’s said. See (and hear) not just the disorder, but the person.